Judge Simon E. Sobeloff, 1894-1973

Main Page | Early Career | Baltimore Trust Investigation | City Solicitor | Return to Private Practice | Solicitor General | Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals | Sobeloff's Personality | Additional Resources

Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals

Nomination Process | On the Court

Nomination Process

Eisenhower first submitted the nomination to the Senate in 1955, and opposition immediately developed, led by Strom Thurmond and Olin Johnston of South Carolina. Although they argued that South Carolina deserved the appointment, they objected primarily to Sobeloff's participation in the school desegregation cases. When Congress adjourned in August, the nomination remained bottled up in Senator James O. Eastland's (D., Miss.) Judiciary Committee. As the session neared a close, the nominee received a letter from his closest friend, Paul Berman, telling him not to worry too much about the "explosion" he had created in South Carolina and reminding him that "four score and fifteen years ago, South Carolina attempted to withdraw from the Union for much less cause" - the election of Abraham Lincoln. Sobeloff's response reveals much about the humor he could bring to the most trying situations:

Isn't it strange how much turmoil a peaceloving man can get into? Here it is only twenty-five years ago that Coleman, J. tested my soul. Now he has left the bench and my friends from South Carolina have taken over. It is interesting to watch their operations and tactics, and while I find it annoying because I am personally involved, looking at it as objectively as I can, it is rather amusing.

Commenting on the news that Congress would adjourn without taking action on his appointment, he reflected:

I feel reasonably philosophical about the whole thing. Justice Harlan was held up for many months, not for anything he did but for something his grandfather did . . . Chief Justice Warren was forced to undergo a long delay . . . They all survived and so will I. [Read the Judiciary Committee Report on the nomination]

Eisenhower

resubmitted the nomination in January 1956. Gearing himself for the ordeal ahead,

Sobeloff compared himself jocularly to a man awaiting his hanging. When the

preacher rushed in and implored the prisoner to renounce the devil and his works,

the prisoner replied, "I'm sorry, but in my position I can't afford to

offend anyone." In the course of the Senate hearings, Southerners opposed

confirmation because of the nominee's views on civil rights, his philosophy

of judicial activism, his refusal to argue the Peters case, and because of trumped

up charges claiming a conflict of interest in the Baltimore Trust case. Senator

Sam Ervin (D., N.C.) testified that Sobeloff's racial views made him "obnoxious"

to the people who would be subject to his judicial rulings and to six of the

ten senators from the states of the Fourth Circuit. In spite of their efforts,

the majority report rejected as "baseless" the charges relating to

the Baltimore Trust investigation and rejected all other objections to the nomination

by a vote of nine to two. After a heated debate on the floor of the Senate which

raged for four hours, the Senate voted to confirm the nomination 64-19. Voting

against him were fifteen southern Democrats and four Republicans, including

Joseph McCarthy, William Jenner, and Herman Welker. "When I mention them,"

Sobeloff reflected years later, "I can take some pride in their opposition."

Four days later, Senator Joseph O'Mahoney (D., Wyo.) claimed that "no man

was ever more thoroughly examined, no man more falsely accused."

Eisenhower

resubmitted the nomination in January 1956. Gearing himself for the ordeal ahead,

Sobeloff compared himself jocularly to a man awaiting his hanging. When the

preacher rushed in and implored the prisoner to renounce the devil and his works,

the prisoner replied, "I'm sorry, but in my position I can't afford to

offend anyone." In the course of the Senate hearings, Southerners opposed

confirmation because of the nominee's views on civil rights, his philosophy

of judicial activism, his refusal to argue the Peters case, and because of trumped

up charges claiming a conflict of interest in the Baltimore Trust case. Senator

Sam Ervin (D., N.C.) testified that Sobeloff's racial views made him "obnoxious"

to the people who would be subject to his judicial rulings and to six of the

ten senators from the states of the Fourth Circuit. In spite of their efforts,

the majority report rejected as "baseless" the charges relating to

the Baltimore Trust investigation and rejected all other objections to the nomination

by a vote of nine to two. After a heated debate on the floor of the Senate which

raged for four hours, the Senate voted to confirm the nomination 64-19. Voting

against him were fifteen southern Democrats and four Republicans, including

Joseph McCarthy, William Jenner, and Herman Welker. "When I mention them,"

Sobeloff reflected years later, "I can take some pride in their opposition."

Four days later, Senator Joseph O'Mahoney (D., Wyo.) claimed that "no man

was ever more thoroughly examined, no man more falsely accused."

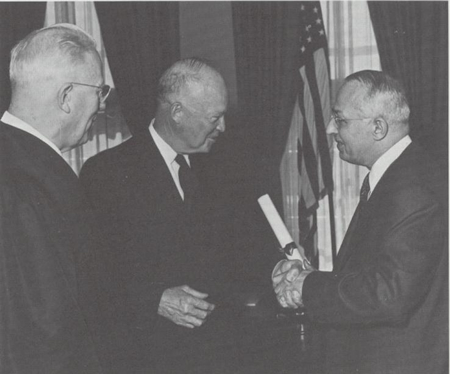

Wearing the same robes he had worn to be sworn in as Chief Judge of the Maryland Court of Appeals, he took the oath of office administered by Judge Soper on July 19, 1956. Slightly less than two years later, Chief Judge John J. Parker died, and on March 17, 1958, Sobeloff succeeded him as Chief Judge of the Fourth Circuit.

Citations to the Congressional Record regarding Judge Sobeloff's nomination:

|

100 Cong. Rec. 1475 (1954) 100 Cong. Rec. A5920 (1954) 100 Cong. Rec. A6373 (1954) 101 Cong. Rec. A5284 (1955) 101 Cong. Rec. A3228 (1955) 102 Cong. Rec. 8369 (1956) |

102 Cong. Rec. 11941 (1956) 102 Cong. Rec. 12819-12866 (1956) 102 Cong. Rec. A516 (1956) 102 Cong. Rec. A961 (1956) 102 Cong Rec. A3629 (1956) 102 Cong. Rec. A4050 (1956) |

On the Court

During his seventeen year tenure, his opinions broke new ground in areas of reform of the criminal justice system, legislative reapportionment, and civil rights. A leading advocate of sentencing reform, he argued that although the law safeguards the rights of a defendant at every stage of the trial, "it leaves him almost completely without protection when he stands before the judge to be sentenced." For the nine of every ten defendants who plead guilty, the nature of punishment was the only issue, yet the law granted "a single judge the sole responsibility for this vital function." Studies uncovered "shocking abuses and irrational disparities," and, as long as the sentencing judge possessed "virtually unrestricted" discretion, "grossly-mistaken, arbitrary, and emotionally-dictated judgments" would continue. The "fantastic vagaries" attendant upon such a system, he concluded, destroyed the "mightiest sanction of the law - respect for the courts." He favored a review of sentences by appellate courts, which were removed from the "emotional overtones" of the trial and tended to view cases from a broader perspective. The very existence of such a review would have a "sobering and moderating effect," which would make its exercise "unnecessary in all but a few cases."

Constrained by the law, he generally declined to review sentences imposed within statutory limits. Nevertheless, he sometimes took an opportunity to suggest to a lower court judge that a sentence should be reconsidered. In one case, a small time gambler, convicted on two charges of gambling, had managed to irritate the trial judge, who responded by giving him concurrent five-year sentences. On appeal, Sobeloff, writing for the Court, upheld one conviction but remanded the case so the judge "might consider the sentence" in light of the partial reversal. The district judge, "heeding the hint" from above, as he put it, reduced the sentence to two years. Such a limited role could not always produce the desired result. A young man with no previous record forged a small check and pleaded guilty to the charge. In the two years between his arrest and the final disposition of the case, his exemplary conduct prompted the probation officer to recommend probation. Nevertheless, the judge sentenced him to three years in prison. Once again speaking for a majority, Sobeloff expressed "a sense of perplexity and concern" over the severity of the sentence and remanded the case, despite the rule that it was not the function of the appellate courts to review sentences. Defiantly, the district judge promptly resentenced the prisoner to a three-year term.

One of the most significant developments of the 1960's was legislative reapportionment to insure that each person's vote carried equal weight. In many states, rural areas dominated state legislatures because of unequal apportionment of representation or antiquated methods of electing representatives. In April 1962, a three-judge panel composed of Sobeloff, Roszel C. Thomsen, and Edward S. Northrop declared invalid a provision of the Maryland constitution fixing at six the maximum number of delegates any one district could have in the House of Delegates. A year later, the same panel ruled that the unit rule convention vote was unconstitutional. Under unit rule, the candidate receiving the majority of the votes received the votes of all the electors from that district. The number of electors, in turn, was based on the representation in the state legislature. Finally, following the lead of the Supreme Court, the judges invalidated Maryland's congressional districts and ordered the drawing of new boundaries.

In his function as a judge, Sobeloff continued his career-long opposition to illegal or excessive exercises of police power. In 1966, Richmond police arrested two men on a charge of "night prowling" (suspicion of moving about at night for some illegal purpose). The arresting officers suspected the men of involvement in a recent chain of burglaries. After the arrests, the policemen discovered that a burglary had occurred earlier that night, and, on the basis of evidence found on the suspects, charged them with that crime. That evidence proved sufficient to have the suspects indicted and convicted. The attorneys for the two men challenged the conviction on the ground that the evidence used at the trial had been illegally obtained. Speaking for the Fourth Circuit, Sobeloff overturned the convictions, ruling that the police had no probable cause for detaining the men in the first place and that evidence garnered as a result of an illegal arrest could not be used in court. A wider scale abuse came to the court's attention a year earlier. Then the Baltimore police, anxious to capture Earl and Sam Veney, two young blacks accused of killing one officer and wounding another, formed a flying squad of fifty to sixty policemen armed with submachine guns, tear gas, and bullet-proof-vests. In the course of nineteen days, they searched some three hundred homes in the black community without search warrants. The NAACP sought an injunction against such searches, but the district judge declined to grant one. Sobeloff wrote the opinion reversing the lower court and enjoining the police from conducting further illegal, blanket searches, characterizing the actions of the police as "the most flagrant invasions of privacy ever to come under the scrutiny of a federal court."

It

was in the area of civil rights, however, that Sobeloff made his greatest mark.

With increasing activism, he sought to secure equal treatment under the law

for black Americans. During Sobeloff's first few years on the court, the Fourth

Circuit reacted cautiously to desegregation. Pleas for cooperation and Judge

John J. Parker's formulation that Brown required desegregation, not integration,

marked the court's initial response. In the closing years of the 1950's, Sobeloff

refused to stay a series of district court orders requiring desegregation of

public schools. Stays would be granted, he told the school boards, only if needed

to work out problems accompanying the conversion to desegregated schools. Since

Virginia's various resistance laws stripped local school authorities of control

when faced with a desegregation order, it was impossible for them to meet that

requirement. After the laws were struck down, Sobeloff did grant a stay of eight

months to the Charlottesville, Virginia School Board in exchange for good faith

implementation of a program to admit blacks to previously all white schools.

However, he denied similar requests from Warren County, Norfolk, and Arlington.

It

was in the area of civil rights, however, that Sobeloff made his greatest mark.

With increasing activism, he sought to secure equal treatment under the law

for black Americans. During Sobeloff's first few years on the court, the Fourth

Circuit reacted cautiously to desegregation. Pleas for cooperation and Judge

John J. Parker's formulation that Brown required desegregation, not integration,

marked the court's initial response. In the closing years of the 1950's, Sobeloff

refused to stay a series of district court orders requiring desegregation of

public schools. Stays would be granted, he told the school boards, only if needed

to work out problems accompanying the conversion to desegregated schools. Since

Virginia's various resistance laws stripped local school authorities of control

when faced with a desegregation order, it was impossible for them to meet that

requirement. After the laws were struck down, Sobeloff did grant a stay of eight

months to the Charlottesville, Virginia School Board in exchange for good faith

implementation of a program to admit blacks to previously all white schools.

However, he denied similar requests from Warren County, Norfolk, and Arlington.

In 1959, Sobeloff headed a three-judge panel which struck down Virginia's school closing law, ruling that it "effectively required a continuation of racial discrimination." The decision broke the back of Virginia's "massive resistance," and for the first time a handful of black children entered previously all white schools in districts all over Virginia. Nevertheless, real integration remained a long way off. In 1960, the Fourth Circuit was still approving grade-a-year plans and allowing academic tests, provided factors of race and color [were] not considered.

Beginning in the early sixties, Sobeloff demonstrated increasing impatience with southern attempts at evasion and became less willing to trade deadlines for good faith. In 1962, Sobeloff handed down two decisions that marked the end of tokenism and moved the Fourth Circuit closer to a policy of enforcing racial equality. The city of Roanoke, Virginia, operated a rigid "feeder" system, which assigned children to one of six sections. Each section was served by an elementary school, and, upon graduation, all of the students attending an elementary school attended a given junior high and then high school. The sections were based not on geography, but on some vague notion of "neighborhood," and the entire black community fell within one section. Writing for the Court, Sobeloff rejected the plan and noted that the Roanoke school system had "disavowed any purpose of using their assignment system as a vehicle to desegregate" their schools. One month later, Sobeloff declared that a similar plan operated by Roanoke County functioned "in flagrant disregard of the Supreme Court's decision" in Brown. That same year, the Fourth Circuit, in a per curiam opinion, struck down Charlottesville's pupil placement plan on two grounds: first, although each student was assigned to a school in his residence zone, pupils whose race constituted a minority in that school could transfer to a school in which their race was a majority; and second, because academic tests were given to black pupils who requested to enroll in predominately white schools, but white pupils were admitted without tests. The end of "minority transfer" removed a major weapon from the southern arsenal of evasion.

The following year, 1963, he persuaded his court to join in ruling that, eight years after Brown, Lynchburg, Virginia's grade-a-year "time schedule [was] too slow and unduly protracted the process of desegregation." In another case, Powhatan County, Virginia maintained two separate schools, each encompassing all grades from elementary through high school. One had a black faculty and black students, the other a white faculty and white students. Sobeloff found that the record disclosed "a persistent purpose and plan on the part of the defendants to deny the plaintiffs their constitutional rights." He ordered that the black children involved in the suit be admitted to the white school at the beginning of the upcoming school term. Moreover, in view of the school board's "long continued pattern of evasion and obstruction," he decided that "justice would not be attained if reasonable counsel fees were not awarded in a case so extreme." Sanford Rosen, a former clerk of Sobeloff's, believed this to be the first school segregation case in which an appellate court awarded counsel fees. That same year saw the Arlington County schools before the Fourth Circuit once again. This time the school board had asked the district court to dissolve the desegregation injunction entered against it in 1956, arguing that since it no longer followed a policy of segregation the injunction was unnecessary. The lower court agreed and entered orders dissolving the injunction. Writing for a three-judge panel, Sobeloff unequivocally reversed the lower court's decision. He brushed aside the board's recent conduct as constituting only a "good faith beginning of compliance" which fell far short of erasing years of obstruction.

The next round of litigation involving the Arlington County schools took a curious turn when, finally acting to fulfill its constitutional obligation, the school board divided the county into two districts, each consisting of approximately 75% white students and 25% black students. A suit filed by the parents of white students charged that the plan "took race into consideration" in assigning students and therefore violated the Constitution. It also charged that the plan denied equal educational opportunities because seventh graders were separated from older students. The district court enjoined the plan. Speaking for the court, Sobeloff overturned the decision saying: "It would be stultifying to hold that a board may not move to undo arrangements artificially contrived to effect or maintain segregation on the ground that this interference with the status quo would involve 'considerations of race.'" He examined the district court judge's conclusion that the plan denied the white students equal protection and found it to be "clearly erroneous." When a school board attempted to eliminate or reduce segregation, "Courts are not commissioned to enter into a debate with school authorities as to which redistricting plan among several is preferable." In stern language he lectured to the district judge, reminding him that "there is no legally protected vested interest in segregation."

In an attempt to undercut a class action suit on behalf of several black children requesting admission to all-white schools in Greene County, Virginia, the Virginia Pupil Placement Board granted several of the requested transfers. As they hoped, the district judge ruled the case moot and refused to enter injunctive relief. The case reached the Fourth Circuit in 1964. Clearly out of patience and wanting to move beyond tokenism, Sobeloff overturned the lower court's decision.

It is too late in the day for this school board to say that merely by the admission of a few plaintiffs without taking any further action, it is satisfying the Supreme Court's mandate for 'good faith compliance at the earliest possible date.

|

|

Seated, left to right: Judge Soper, Chief Judge Sobeloff,

Judge Haynsworth. Standing, left to right: Judge Bryan, Judge Boreman,

Judge Bell

|

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 mandated an end to segregation, and the Supreme Court ruled in 1968 that school districts must integrate, not merely desegregate, to meet the requirements of Brown. During these years, consensus on the Fourth Circuit began to break down. Sobeloff reached the age of mandatory retirement and resigned as Chief Judge at the end of 1964, and, although he remained an active circuit judge, he wrote only one more opinion for a majority in a school desegregation case. In fact, he prepared many more concurrences and dissents than he actually filed; often the circulation of his separate opinion provided the impetus for altering the thrust of a majority opinion, making it unnecessary for him to write. Moreover, to preserve credibility, he often chose to withhold his own opinion, even if the majority would not compromise to his satisfaction. Although he often could not command a majority on the Fourth Circuit, he enjoyed a remarkably high rate of success in directing cases to the Supreme Court. One commentator noted that a dissent by Sobeloff was as good as an appeal for certiorari.

In 1964, a majority of the Fourth Circuit upheld a freedom of choice plan adopted by Richmond, Virginia, which allowed each student to select his or her own elementary school and also permitted transfers. In upholding the plan the majority ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment did not prohibit "segregation as such;" rather "the proscription is against discrimination." Sobeloff concurred in part and dissented in part. For him, the plan was acceptable only as an interim measure, subject to immediate reevaluation by the district court, and even then only "in hope of encouraging the Board so to administer the Resolution as to make it a genuine and effective plan of desegregation." He disagreed with the majority's construction of the Fourteenth Amendment, asserting instead that school authorities had an affirmative obligation to integrate and not merely to desegregate. He also dissented from the majority's refusal to order an immediate inquiry into the desegregation of the school district's faculty. The Supreme Court granted certiorari and in a per curiam opinion reversed and remanded, accepting Sobeloff's position on faculty allocation.

Sobeloff continued his attack on freedom of choice plans with special concurrences in two cases handed down in 1967.

Freedom of choice' is not a sacred talisman; it is only a means to a constitutionally required end - the abolition of the system of segregation and its effects. If the means prove effective, it is acceptable, but if it fails to undo segregation, other means must be used to achieve this end. School officials have the continuing duty to take whatever action may be necessary to create a 'unitary, non-racial system.

Once again, the Supreme Court accepted the invitation to review, and once again it adopted Sobeloff's position as its own.

In the spring of 1970, District Judge James B. McMillan ordered the public schools of Charlotte, North Carolina and surrounding Mecklenberg County to desegregate - not piecemeal, but totally. Since 71% of the school population of the area was white and 29% black, the approximate ratio of attendance at each school should reflect those figures. He ordered attendance zones altered and bussing to achieve "racial balance." For his action, McMillan received death threats and had crosses burned in front of his home. The Fourth Circuit cut back on McMillan's order and ruled that the plan for massive bussing placed an "unreasonable burden" on the school districts. Sobeloff dissented; he would have confirmed McMillian's plan. In a unanimous opinion written by Chief Justice Burger, the Supreme Court upheld McMillan's decision. Publicly, Sobeloff expressed his gratification that "the new Court - like the old Court - has stood as a unit" on school desegregation. Privately, he must have felt gratification for much more.

Sobeloff's last two school decisions addressed not only the issue of school integration, but the problem of racism in American society. In the first, a case arising in Claredon County (one of the school systems involved in the Brown decision), the Fourth Circuit upheld a district court order requiring the implementation of a comprehensive plan of desegregation. Three of his brethren dissented in part; fearing white flight, they would have modified the plan. Sobeloff filed a separate concurrence in answer to the dissenters. Their proposal, he wrote, was morally and constitutionally untenable. At the same time, it offered a premium for community resistance. "The linchpin of the dissent," he wrote, was "the notion that, ideally, the goal of desegregation should be to achieve an 'optimal mix,' consisting of a white majority" and that "desegregation should not go so far as to put whites in minority situations." The dissent, he claimed, constituted "a direct attack on the roots of the Brown decision." Central to the dissenters' position was the notion that "the value of a school depends on the characteristics of a majority of its students, and superiority is related to whiteness, inferiority to blackness." He argued that, although couched in terms of "socioeconomic class" and the creation of a middle class milieu," such arguments rested on the generalization that, educationally speaking, white pupils are somehow better or more desirable than black pupils."

This premise leads to the next proposition, that association with the white pupils helps the blacks and so long as whites predominate does not harm the white children. But once the number of whites approaches minority, then association with the inferior black children hurts the whites and, because there are not enough of the superior whites to go around, does not appreciably help the blacks.

Stressing that this idea was "no more than a resurrection of the axiom of black inferiority as a justification for a separation of the races," he ended with the assertion that desegregation was not "founded upon the concept that white children are a precious resource which should be fairly apportioned." Segregation, he declared, "is forbidden simply because its perpetuation is a living insult to black children and immeasurably taints the education they receive."

Appropriately enough, Sobeloff's last decision involving school desegregation found him dissenting once again. He claimed that carving out new school districts to achieve a racial composition acceptable to the white community amounted to another "evasive tactic" to avoid the clear mandate of Brown. The Fourth Circuit had held that district courts were to intercede only if they found that "racial considerations were the primary purpose in the creation of the new school units." Sobeloff suggested a different test. He believed that if a "challenged state action has a racially discriminatory effect, it violates the equal protection clause unless a compelling and overriding legitimate state interest is demonstrated." Relying on a standard familiar to tort law, he argued that a person is responsible for the natural consequences of his actions. On both of these points, the Supreme Court for a last time turned a Sobeloff school dissent into law. At the end of 1970, Sobeloff took qualified retirement, and, although he continued to carry a full case load until his death in 1973, most segregation cases were heard en banc, and senior judges did not usually sit on them.

School cases clearly constituted the bulk of the segregation cases Sobeloff heard on the Fourth Circuit, but they were not the only ones. In 1963, he ruled that hospitals receiving public funds could not practice discrimination. In addition, discrimination against blacks often became inextricably intertwined with the rights of the criminally accused. Such was the case of Elmer Davis, an illiterate black man arrested for the brutal rape and murder of an elderly woman. The police held him for sixteen days, during which time he was allowed no contact with counsel, friends, or family. Nor was he informed of his right to counsel. On the sixteenth day, a policeman led Davis in "prayer," after which Davis confessed. Based on that confession, Davis was found guilty and sentenced to die in the gas chamber. When the Fourth Circuit upheld the validity of Davis' confession Sobeloff and another judge dissented. According to Sobeloff, "police solicitude for the defendant's spiritual welfare would be less suspect if the police, so eager to provide a religious comfort for a man who 'did not know how to pray' had sent for a minister then, instead of having a policeman play the role of a minister." Noting that Davis had confessed immediately following the prayer session, Sobeloff wryly observed that "the officer's prayer, at least, was answered." Skeptical of the prayer as an impetus to confession, he thought it far more reasonable to conclude "that the confession came in response to the pragmatic appeal addressed to Davis in his predicament by the lieutenant: Davis, go in there and sign that paper so that you can get something to eat and get a hot bath." Adopting Sobeloff's position sub silento, the Supreme Court overturned Davis' conviction.

Main Page | Early Career | Baltimore Trust Investigation | City Solicitor | Return to Private Practice | Solicitor General | Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals | Sobeloff's Personality | Additional Resources