The Legal Papers of Dallas Nicholas and William Gosnell

The collection provides a rare view into a segment of society that has been, for the most part, ignored: the world of the mid-twentieth-century, African American attorney. As African American attorneys, Nicholas and Gosnell were among the first at a time when their numbers were few, yet they managed to make notable contributions in the struggle for civil rights. Within the African American community, these men, by benefit of their profession and knowledge, held positions of power and influence, and as such worked to improve their community from within.

Background | Practice Areas | Collection Information

Background

Founded in 1935, the law firm of Dallas F. Nicholas and William I. Gosnell was a general practice firm. Their association was a loose one; at times, they worked closely together, and the files reflect this with content and communication from both in a single file. At other times, they seemed to operate separately from one another with unique business letterheads and separate clients. During its history, the firm also included an associate partner named U. Theodore Hayes, who would go on to become the first African American Hearings Master in the Baltimore City Circuit Court.

Nicolas and Gosnell were both active in the civil rights movement in Maryland and Baltimore. William I. Gosnell worked closely with Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP in the case of University v. Murray, 169 Md. 478 (1936), which desegregated the University of Maryland School of Law. In 1934, Gosnell met Donald G. Murray, a graduate of Amherst College, and introduced him to Thurgood Marshall as a potential plaintiff. Murray had applied to the University of Maryland School of Law and been rejected based on his race. Murray subsequently appeared with Gosnell, Thurgood Marshall, and Charles Houston to challenge Maryland's exclusionary policy before a Baltimore City judge who ordered the law school to admit Murray immediately.

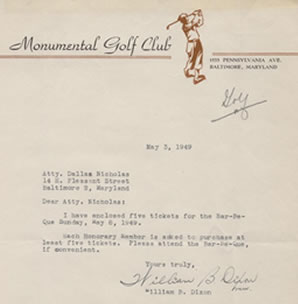

One

of Dallas Nicholas' major contributions to the fight for civil rights and equality

(documented in this collection) concerns the equality of recreational facilities

in Baltimore, specifically golf courses. Both Nicholas and Gosnell belonged

to an organization called the Monumental Golf Club, which consisted of a diverse

group of African Americans, including attorneys, doctors, teachers, and teens.

In 1934, the Monumental Golf Club became frustrated with the poorly-maintained,

nine-hole course that was assigned to African Americans. Dallas Nicholas, acting

as the Monumental Golf Club's attorney, initiated a legal battle with the Baltimore

Board of Recreation and Parks that would span two decades and culminate in Boyer

v. Garrett, 183 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1950).

One

of Dallas Nicholas' major contributions to the fight for civil rights and equality

(documented in this collection) concerns the equality of recreational facilities

in Baltimore, specifically golf courses. Both Nicholas and Gosnell belonged

to an organization called the Monumental Golf Club, which consisted of a diverse

group of African Americans, including attorneys, doctors, teachers, and teens.

In 1934, the Monumental Golf Club became frustrated with the poorly-maintained,

nine-hole course that was assigned to African Americans. Dallas Nicholas, acting

as the Monumental Golf Club's attorney, initiated a legal battle with the Baltimore

Board of Recreation and Parks that would span two decades and culminate in Boyer

v. Garrett, 183 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1950).

In 1936, after two years of battling the Board, Nicholas and the Monumental Golf Club achieved some success when the Board agreed to grant African Americans exclusive use of the 18-hole Carroll Course. Being awarded an 18-hole course of their own wasn't the end of the battle for Nicholas and the Monumental Golf Club; now they fought for equality in the conditions of their course and the upkeep of the guest house as well as the right for racially integrated play on those links. That fight and its resulting gains were well worth it for the Monumental Golf Club and Baltimore's African American golfers, who were very active in both the sport and in Baltimore society. This can be seen in the Monumental Golf Club Schedule for the year 1938, which is part of the collection. Adult men and women as well as teen golfers were active from April through October, holding lessons, tournaments, and hosting African American golfers from other cities.

Like other attorneys in Baltimore, both Nicholas and Gosnell joined city, state, and national bar associations to keep abreast of changes in the field, as well as to network with colleagues. Because African Americans could not participate in the same professional organizations as whites they created their own. The National Bar Association, of which both Nicholas and Gosnell were members, was one such group.

African American attorneys in Baltimore had their own association as well. The Monumental City Bar Association (MCBA) began in the mid-1930s and was very active in the community. The MCBA would join together with other organizations to host events, such as its 18th Annual Convention held at the Masonic Temple in Baltimore, November of 1946. Both Dallas Nicholas and William Gosnell took an active role in the planning and implementation of this event. African American attorneys from across the nation attended, including Raymond Pace Alexander, Charles H. Houston, and Thurgood Marshall.

By the mid-1940s, the Gosnell and Nicholas firm was ready to expand. After communication with other African American attorneys and community leaders, they decided upon Cambridge, Maryland. This office was a successful venture. Both attorneys shuttled back and forth between Baltimore, where they maintained the bulk of their work, and the Eastern Shore, for the remainder of their professional lives.

Unfortunately, one area that is not well reflected in the legal files presented here is the business records of Nicholas and Gosnell. While there is a great deal of documentation about the costs incurred for a particular case or issue, there is little in the way of documentation about the overall firm organization, its income or expenses.

The partnership ended in 1966 with the death of Dallas Nicholas (see the Afro American Newspaper, October 8, 1966). William Gosnell passed away in 1978 (see the Afro American Newspaper, April 1, 1978).

Practice Areas

Divorce. For the firm of Nicholas and Gosnell, family law comprised a large part of the caseload. As a result, both attorneys handled numerous divorce requests, from clients both in-state and out-of-state. The collection reflects the vast range of issues faced in dealing with a divorce case.

Personal Injury. When they started their practice in 1935, personal injury and workman's compensation claims comprised a small portion of Nicholas and Gosnell's workload. One company, the Baltimore Transit Company, appears repeatedly in this collection as a legal party. An example of a personal injury case involving the Baltimore Transit Company is that of Emma G. Arrington vs the Mayor and City Council. Mrs. Arrington was injured when she slipped and fell at a public bus stop. The case file includes her initial claim statement documentation reporting the incident to the Baltimore Transit Company, the original defendant. The Transit Company denied responsibility, forcing Gosnell to look to the city of Baltimore as the responsible party.

Estate Administration and Probate Law. Nicholas and Gosnell's estate administration and probate law cases reflect the giving practices of some African Americans in Baltimore. For example, there are insurance policies made out to various organizations as beneficiaries, including the Odd Fellows Mutual Endowment Association. This particular bequest allowed William Gosnell to locate Mr.Tinsdale's heir and to distribute additional funds to settle the estate.

When closing out the estate of another client, William Gosnell discovered the person's enlistment record, for service performed during World War I. Gosnell used this information to locate military death benefits for the decedent's heirs. Other details can be learned from this document including the client's date of enlistment, July 15, 1918; his rank of Noncommissioned officer; his company, the 13th Service Company; his civilian occupation of painter; pertinent medical information, marital status, and physical description.

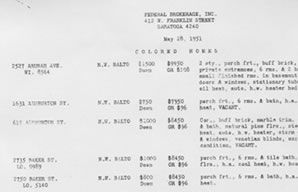

Real Estate Business. Many attorneys of this era were also real estate agents and participated in

a variety of real estate businesses. Property management, mortgage financing,

selling or purchasing property were all areas in which these attorneys dealt.

One example of this business is an expense sheet from the estate of Dr. William

C. McCard, father of Nicholas' first wife, Grace "Chita" McCard. Dr.

McCard was a successful physician with a practice in Baltimore. In addition

to his practice, Dr. McCard owned 23 rental properties, managed by his son-in-law

Dallas F. Nicholas. This expense sheet is from the period following the doctor's

death and lists all of his properties and the income and expenses of each.

Real Estate Business. Many attorneys of this era were also real estate agents and participated in

a variety of real estate businesses. Property management, mortgage financing,

selling or purchasing property were all areas in which these attorneys dealt.

One example of this business is an expense sheet from the estate of Dr. William

C. McCard, father of Nicholas' first wife, Grace "Chita" McCard. Dr.

McCard was a successful physician with a practice in Baltimore. In addition

to his practice, Dr. McCard owned 23 rental properties, managed by his son-in-law

Dallas F. Nicholas. This expense sheet is from the period following the doctor's

death and lists all of his properties and the income and expenses of each.

Baltimore's real estate market operated under Jim Crow Laws well into the 1970s. African Americans were not allowed to move into predominately white areas and vice versa. In order to facilitate this separation, there were listings for homes available to both races with African Americans forced to rely on the "Colored Homes Listing." Nicholas and Gosnell would have used lists such as this to guide prospective homeowners in their choices.

Income Tax Preparation. This service was a staple for attorneys Nicholas and Gosnell. They provided tax services such as preparation, to private individuals as well as businesses. Many of their customers were regulars who returned again and again, sometimes for decades.

Collection Information

Please contact the library to make an appointment to access this collection.

Professor Larry Gibson donated the collection to the Thurgood Marshall Law Library, The University of Maryland School of Law, in 2002. Processing began in the fall of 2002 and was completed in the fall of 2004. Project staff included Lauren Bailey, Erin Holcombe, and Bill Sleeman, Asst. Director for Technical Services.

Material is arranged and labeled in the original filing order by cabinet (left to right) and drawer (top to bottom). While a chronological arrangement generally predominates, there is, as the business of particular clients ebbed and flowed, some interfiling of materials.

Access to the collection is by appointment only. Contact the Library at 410-706-6502.

Attorney/Client privilege. Library Staff at the Thurgood Marshall Law Library have examined current practices at several institutions, reviewed the ABA rules on attorney/client privilege and has discussed the issue with historians, archivists and attorneys. With this collection the Library has decided to open all material dated 30 years or more from the dissolution of Nicholas' and Gosnell's partnership. Researchers should secure the permission of any identifiable family members when considering the publication of specific personal information from the collection.

Photocopying of non-fragile material is available. Tax documents and individual financial statements may not be photocopied. Adoption records and related information are generally closed but can be accessed on a case-by-case basis. Please contact the library to discuss permission.

Permission to reproduce or quote from the collection generally in published research in any format may be requested in writing from the Thurgood Marshall Law Library, University of Maryland School of Law, Special Collections, 501 West Fayette Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201.

Cite as: The Legal Papers of Dallas Nicholas and William Gosnell. Thurgood Marshall Law Library, The University of Maryland School of Law.